As climate change causes summer temperatures to rise, many cities are looking to trees to provide health benefits and counteract the effects of urban heat events. Yet often the tree canopy is uneven, a legacy of inequitable development patterns and zoning. To ensure that the health and climate benefits of trees can be enjoyed by all residents, cities must be intentional in how they plan, plant, and care for their urban forests.

In Bridgeport, Connecticut, community organizations are working with the municipal government to plant more trees and nurture them to ensure they reach maturity. Bridgeport, a port city on the rail line between New York City and Boston, was once a hub of Connecticut’s manufacturing industry. However, like many former industrial cities, its economy declined in the late 20th century. The city’s East Side in particular suffered the effects of suburbanization and 1960s urban renewal policies, which demolished many Black and immigrant neighbourhoods to make way for highway projects and new development, some of which never materialized. One legacy of this era is significantly lower tree cover and less access to green spaces on the East Side, where the population is more diverse, and less wealthy, than the city as a whole.

Many of the benefits of trees — such as shade, cooling, and pollutant mitigation — are highly localized. To achieve the benefits from tree cover, trees need to be planted not at the scale of cities but of neighbourhoods, blocks, and even homes.

Groundwork Bridgeport

Groundwork Bridgeport is a community-based organization founded in 1998 as one of the first of a national network of non-profits dedicated to reclaiming abandoned industrial sites and underused lots to create economic development opportunities and spaces for recreation and beautification. They aim to bring the benefits of tree cover to all, starting with the East Side. A small, local organization, Groundwork Bridgeport worked with the EDDIT data storytelling team to build momentum around their work, communicate the importance of trees and tree canopy cover, and engage partner organizations and the public to get involved through volunteering, financial support, or tree adoption.

A key part of the organization’s mission is improving the overall well-being of residents in communities that have historically been neglected, denied resources, or otherwise ignored over the years. One of their priorities is mobilizing volunteers and partners in the East Side neighbourhood to advocate for more green spaces. In addition to telling their story with the data, the organization has focused on their local roots and role in building connections to encourage greater community involvement in environmental stewardship.

Historical neglect and tree equity

Access to urban trees and green spaces is not equitably distributed. The non-profit organization American Forests developed a tree equity score that identifies disparities in different populations’ access to trees. The score integrates environmental characteristics, including tree canopy, building density, and surface temperature, as well as socioeconomic and demographic variables such as income, employment, race, age, language, and health. The concept of tree equity has been widely adopted as a way to highlight differences in access to green spaces more broadly.

A significant finding from this work is that neighbourhoods with a majority of people of colour have on average 33 percent less tree canopy than majority white neighbourhoods. Communities with high levels of people living in poverty have 41 percent less tree cover than wealthier areas. [1] Another nationwide analysis of land cover in densely populated areas found that neighbourhoods highly segregated by race had relatively less tree canopy, particularly among Hispanic and Asian communities. The same study found that neighbourhoods with a high percentage of renters had less tree cover than those with high levels of home ownership. [2]

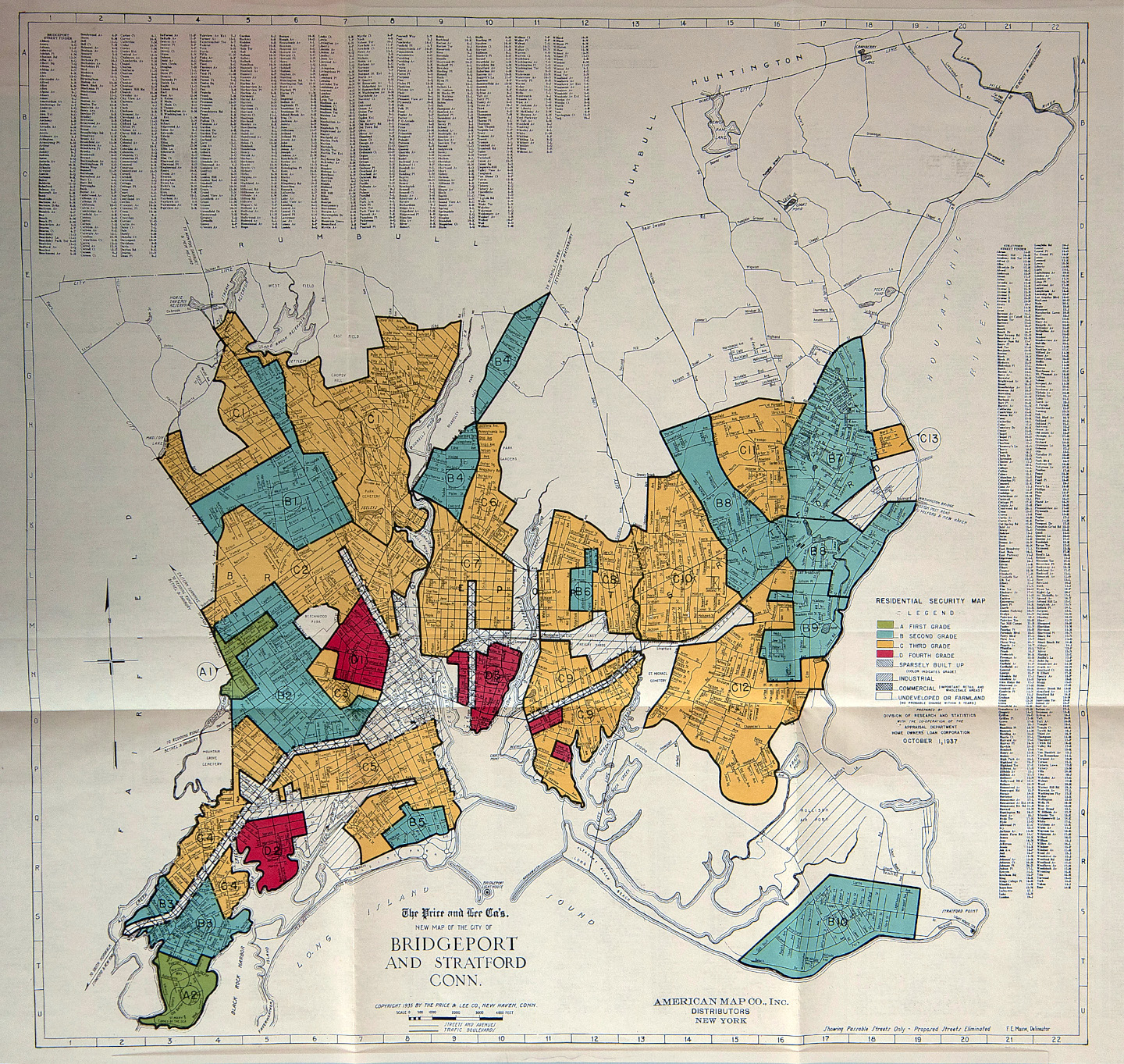

Variation in tree cover reflects the legacy of historic government disinvestment in communities with more racial minorities. [3] Neighbourhoods in Bridgeport that were historically redlined have less tree cover today than neighbouring areas. Redlining was the practice of withholding loans and other financial resources from neighbourhoods based on their racial or ethnic characteristics, and was common in American cities in the 1930s through the 1960s. [4]

Illustrating the impact of trees using data

In many cities, funding for tree planting initiatives and maintenance comes from local government, so the Bridgeport data story focuses on communicating the benefits of investing in trees to decision-makers in municipal departments, including Parks & Recreation and Health, as well as members of city council.

A first step is to establish a baseline of the existing tree cover, which can be done for many cities using publicly available data about the city’s Tree Equity Score. This information can be explored via an interactive online tool that allows users to input tree cover goals and see heat metrics and tree cover gaps. The tree canopy data are sourced from Google's Environmental Insights Explorer, which uses machine learning to analyze imagery captured over different years at a fine resolution. Users can download this baseline of tree canopy data and create additional layers that incorporate local data from other sources highlighting how trees affect climate resilience, health, and public safety.

The benefits of trees: climate impacts

Green spaces and trees planted along sidewalks and roads have a variety of positive effects in urban environments. Trees absorb pollutants like carbon monoxide and dioxide, ozone, nitric oxide and nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide from the atmosphere, reducing cities’ emissions. They also help to filter out fine particulate matter (PM2.5), generated by vehicle tailpipe emissions and industry, which is one of the most deadly forms of air pollution. [5] These air purification effects are magnified in areas with warmer weather, where growing seasons and time in leaf are longer. [6] Organizations looking for data to support work on trees’ role in pollution mitigation can use air quality data from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), which is available at the county level for roughly a third of U.S. counties.

Trees also help to mitigate the effects of urban heat islands (UHI), the phenomenon where cities experience warmer temperatures than surrounding areas due to the prevalence of impermeable surfaces like asphalt and concrete, and air pollution from transportation and energy uses. [7] Trees help to alleviate UHI effects in two ways: by providing shade that reduces the ambient air temperature, and through evapotranspiration, in which they absorb energy from the air. Shade in particular has significant cooling effects, reducing urban daytime temperatures by 4 degrees C (7 degrees F) and nighttime temperatures by up to 12 degrees C (22 degrees F). [8] These lower temperatures reduce the need for air conditioning and help limit urban energy consumption. Trees also provide an insulating role in winter, which can reduce heating use.

Bringing this concept to life with visual data, this thermal imagery captured in Bridgeport shows the stark difference in ground temperature (roughly 22 degrees C or 40 degrees F) between an uncovered paved path and an adjacent area shaded by trees. Many cities have community-based heat monitors where similar information is available.

Another benefit of trees and other green spaces is that they absorb water, reducing the risk of flooding, erosion, and the degradation of urban waterways. They also help to break up soil, allowing it to retain more water. Trees combat nutrient runoff in stormwater by absorbing phosphorous and nitrogen from lawn fertilizers and pet waste, preventing them from entering waterways and leaching into groundwater. This reduction in stormwater nutrient runoff has been linked with decreased municipal water treatment costs.

The health benefits of tree cover

Trees also provide a number of health benefits. In filtering pollutants from the air, they make it easier to breathe, which can reduce the rate of asthma. More urban green space is also associated with decreased risk of stroke and coronary heart disease. Proximity to trees can alleviate some of the effects of cardiovascular problems and lower the stress associated with noise pollution. [9] Overall, increasing tree canopy can lead to lower mortality rates from disease.

Urban green spaces with tree cover also improve physical health outcomes by providing safe, shaded, attractive places to walk, run, and play, offering both health and lifestyle benefits. Physical activity is linked with extended life expectancy and more outdoor playing time for children. [10] In addition to physical health outcomes, trees also have a positive impact on mental health. One study found that people who lived within 100 metres (325 feet) of street trees had lower levels of stress and anxiety, and less need for antidepressants, with stronger effects in lower-income communities. [11] Trees and green spaces have also been linked to stronger community trust and collective efficacy, as attractive outdoor areas encourage more neighbourhood interaction and positive social engagement. [12] Organizations looking to show what effects trees can have in their communities can use the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Places dataset, which tracks many health metrics at the census block group level and which can be mapped and analyzed relative to Tree Equity Score data.

Moving from challenges to opportunities

Despite their numerous health and environmental benefits, there are some challenges to planting trees in urban environments. For example, there is a common idea that trees can block sight lines for law enforcement or hide criminals, which has been used by various groups to argue against increasing tree cover. [13] However, a significant number of studies, including one conducted at the census block level in New Haven, Connecticut in 2015, found that greater tree cover was associated with lower levels of both violent and property crime. [14] This finding remained significant even after accounting for factors like household income, race, renter-to-owner ratio, and vacancy rates.

Another challenge is the lack of space for tree planting in low-income neighbourhoods, which tend to have narrower sidewalks, less open space, and more impervious materials such as concrete and asphalt. [15] These areas also tend to have higher levels of population density and development, and therefore less available space overall. [16] Many homes are rented, meaning property owners are not on site to approve plantings.

However, despite these challenges, there is potential for trees to have a particularly significant impact in lower-income neighbourhoods, given that these areas tend to have more limited access to air conditioning and outdoor space, and a higher share of the population that does physical work outdoors. [17] By cooling the surrounding environment, trees can mitigate the harmful effects of extreme heat to which low-income communities are particularly vulnerable.

Because of the challenges associated with planting in lower-income communities, many cities have expanded their tree cover opportunistically, often choosing to plant where they have permission, easy access to land, and good conditions. By failing to develop a strategic approach to planting trees, some cities have exacerbated existing inequities in tree cover and failed to ensure long-term community or maintenance support. Approaches to urban tree planting may also not account for changing climate and water cycles, which can lead to the death or removal of trees, ultimately wasting limited resources. [18] To enjoy the full heat, health, and environmental benefits from their efforts, cities need to create strategic and coordinated tree planting programs with partners at all stages, from planning to implementation and maintenance.

Grassroots groups like Groundwork Bridgeport help make tree cover expansion programs successful in the long term by ensuring residents play an active role in tree planting in their own neighbourhoods. For example, Groundwork Bridgeport works with local community leaders to make sure that trees align with resident preferences, even engaging them in the act of planting. A variety of other non-profits have created resources for potential tree stewards — those who care for trees — including a guide explaining how to select trees that are appropriate for a given space, as well as tips on how to plant, maintain, and water them. A community-based approach is essential. [19]

Given trees’ myriad environmental benefits, there is a growing movement to build more of this “green infrastructure” in urban areas. Additional opportunities for tree planting might include creating a green space requirement for new building developments, replacing parking spaces with greenery, and adding bus bulbs (curb extensions that bring bus stops in line with a parking lane). These all come with trade offs, financial and otherwise, which must be negotiated with communities. In the meantime, projects like the EDDIT-Groundwork Bridgeport case help urban leaders and residents understand the benefits and challenges of planting trees, and target priority investment areas so that all can experience a healthier, greener future.

The authors would like to thank Karen Chapple, Michelle Zhang, Julia Greenberg, and Evelyne St-Louis for their contributions to editing and informing this case study.

References

American Forests, “Nationwide Evaluation Of Tree Cover Shows Huge Opportunity To Reduce Heat Exposure And Boost Air Quality And Employment,” PR Newswire (blog), June 22, 2021, URL.

↑Bill M. Jesdale, Rachel Morello-Frosch, and Lara Cushing, “The Racial/Ethnic Distribution of Heat Risk–Related Land Cover in Relation to Residential Segregation,” Environmental Health Perspectives 121, no. 7 (July 2013): 811–17, URL.

↑Meen Chel Jung et al., “Legacies of Redlining Lead to Unequal Cooling Effects of Urban Tree Canopy,” Landscape and Urban Planning 246 (June 1, 2024): 105028, URL.

↑Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2017).

↑The Nature Conservancy, “Planting Healthy Air: A Global Analysis of the Role of Urban Trees in Addressing Particulate Matter Pollution and Extreme Heat,” November 4, 2016, URL.

↑David J. Nowak, Daniel E. Crane, and Jack C. Stevens, “Air Pollution Removal by Urban Trees and Shrubs in the United States,” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 4, no. 3 (April 3, 2006): 115–23, URL.

↑Min Jiao et al., “Optimizing the Shade Potential of Trees by Accounting for Landscape Context,” Sustainable Cities and Society 70 (July 1, 2021): 102905, URL.

↑Peter James et al., “A Review of the Health Benefits of Greenness,” Current Epidemiology Reports 2, no. 2 (June 1, 2015): 131–42, URL.

↑Mark McCord, “This Simple Addition to a City Can Dramatically Improve People’s Mental Health,” World Economic Forum (blog), April 6, 2021, URL.

↑Deborah A. Cohen, Sanae Inagami, and Brian Finch, “The Built Environment and Collective Efficacy,” Health & Place 14, no. 2 (June 1, 2008): 198–208, URL.

↑Sandra Bogar and Kirsten M. Beyer, “Green Space, Violence, and Crime: A Systematic Review,” Trauma, Violence & Abuse 17, no. 2 (2016): 160–71, URL.

↑Kathryn Gilstad-Hayden et al., “Research Note: Greater Tree Canopy Cover Is Associated with Lower Rates of Both Violent and Property Crime in New Haven, CT,” Landscape and Urban Planning 143 (November 1, 2015): 248–53, URL.

↑Rachel Danford et al., “What Does It Take to Achieve Equitable Urban Tree Canopy Distribution? A Boston Case Study,” Cities and the Environment (CATE) 7, no. 1 (February 24, 2014), URL; Jesdale, Morello-Frosch, and Cushing, “The Racial/Ethnic Distribution of Heat Risk–Related Land Cover.”

↑Edith B. de Guzman, Francisco J. Escobedo, and Rachel O’Leary, “A Socio-Ecological Approach to Align Tree Stewardship Programs with Public Health Benefits in Marginalized Neighborhoods in Los Angeles, USA,” Frontiers in Sustainable Cities 4 (2022), URL.

↑de Guzman, Escobedo, and O’Leary, “A Socio-Ecological Approach to Align Tree Stewardship Programs.”

↑