In today's Toronto and surrounding municipalities, it is more common for someone's mother tongue to be a language other than English. A longtime hub for immigration to Canada, the region is one of the world's most multicultural and, as a result, has long been home to dozens of languages from around the globe.

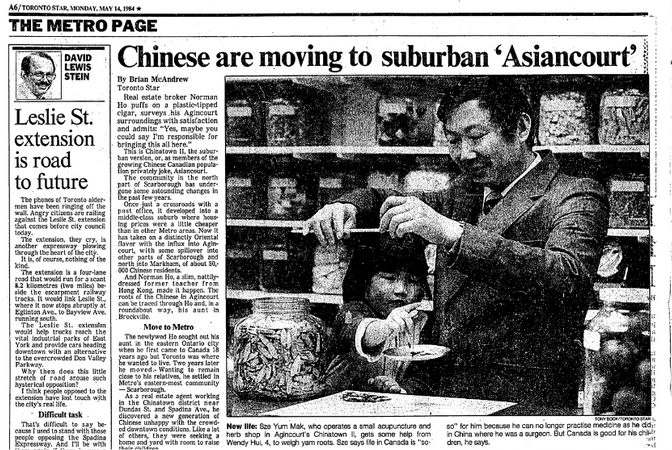

Whether Italian or Punjabi, Yiddish or Tagalog, many languages have arrived, grown, and sometimes declined over the last several decades. Some, such as the Chinese languages, have expanded into the suburbs as immigration and settlement patterns shifted. Others, like Greek, are slowly fading away due to a lack of new immigrants and an aging community.

Each of these languages belongs to a community, and each community has its own story of arrival, settlement, and cultural life in the region.

Below, we map first-language speakers? for many different languages across the region in 1971, 1996, and 2021. For each language, we share a brief account of how these communities formed and changed over time, alongside selected images from different periods. Choose a language below and scroll to explore its story.

Data & Methodology

Language data are from the Canadian census and were obtained from UNI-CEN. After reviewing availability across multiple decades, we selected a subset of census years (1971, 1996, and 2021) and languages for which data were consistently available and represented a substantial number of speakers. Due to irregularities and gaps in historical census reporting, additional languages and years could not be included.

We chose to use "First Language" ("Mother Tongue") rather than "Knowledge of", as the latter is inconsistently reported in earlier census years. "First Language" denotes the language learned at home in childhood and still understood by the person, whereas "Knowledge of" refers to whether a person can conduct a conversation in a given language. We previously produced an interactive map on knowledge of languages and the GTHA, and Alex McPhee created a map of mother tongues in Toronto.

It is important to note that "First Language" does not fully capture multilingual households or everyday language use, particularly in later generations. It's only in more recent censuses that respondents may choose multiple first languages, besides recording other linguistic information.

Rather than mapping census geographies (such as census tracts), we used population-weighted aerial interpolation to generate a uniform grid of 1 km squares across the Toronto region. This approach allowed us to create smooth contour maps using Observable's Plot library.

We limited our geography to Toronto and major surrounding municipalities to balance regional coverage with population and importance. Our final list of municipalities were: Toronto, Mississauga, Brampton, Vaughan, Richmond Hill, Markham, Pickering, and Ajax.

All code and processed data used in this project are publicly available in the accompanying GitHub repository.

Acknowledgements

A special thanks to the many people who contributed context, insight, and background on different linguistic communities: Francesca Allodi-Ross (Spanish), Vidhya Elango and the JCCC (Japanese), Gabriela Pawlus Kasprzak (Polish), Naomi Nagy and the HLVC team (Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Italian, Russian, Spanish, Tagalog), Serene Tan (Chinese), Aloysius Wong (Tagalog), Miru Yogarajah (Tamil), and Michelle Zhang (Chinese).

We also thank Nael Shiab for his clear and intuitive methods section in his project on rising temperatures in Canada, which provided inspiration for both the methodological approach and visual design of this project.